Cyanuric Acid (CYA), also called stabilizer or conditioner, protects chlorine from sunlight. But CYA is a double-edged sword, causing a dramatic impact on chlorine efficacy and sanitization. CYA is so important to keep to a minimum that we decided to make Minimal CYA our fourth Pillar of Proactive Pool Care.

Cyanuric Acid Facts

Cyanuric acid (CYA) is well known in the pool business. It serves as a protection shield for chlorine against sunlight. The Sun’s ultraviolet rays degrade chlorine very quickly, creating a problem for outdoor pools. Studies show that sunlight can wipe out chlorine by 75-90% in a matter of two hours. The half-life of chlorine—when exposed to direct sunlight—is about 45 minutes. That means half your chlorine is gone in 45 minutes. After another 45 minutes, another half of your chlorine is gone. So on and so forth.

CYA impacts water in so many ways, we would be doing a disservice to the industry to ignore it. Understanding CYA is a cornerstone of what we teach, and there is a growing body of research available online1.

A chlorine stabilizer is needed, otherwise, you will be using (and losing) chlorine all day, every day. Chlorine used to be added daily up until the discovery of cyanuric acid in 1956. This article will outline a few things you should know about cyanuric acid.

1. How does cyanuric acid work?

The cyanuric acid molecule is a hexagon with alternating Nitrogen and Carbon atoms. It allows for three molecules of chlorine to attach to the nitrogen, forming a weak nitrogen-chlorine bond (N-Cl). Because the N-Cl bond is weak, it allows for chlorine to let go of CYA when it has something to oxidize or kill. When attached to CYA, however, chlorine is protected from sunlight. Cyanuric acid is kind of like sunscreen for chlorine.

We know the Nitrogen-chlorine (N-Cl) bond is weak because the chlorine attached still shows up in a free chlorine test. If the bond were stronger—like that of chloramines and other disinfectant byproducts—chlorine would only show up on a total chlorine test, not free chlorine.

A metaphor: Imagine a floating raft that chlorine holds onto. When it needs to leave the raft to oxidize or kill a germ, chlorine simply lets go of the raft…and another chlorine molecule will take it’s place and grab the raft. As long as chlorine is holding onto the raft, it’s protected from sunlight. When it lets go, it’s active free available chlorine, but vulnerable to sunlight.

Cyanuric acid is available as a granular solid and as a liquid (sodium cyanurate). Most commonly, however, cyanuric acid is found in stabilized chlorines dichlor and trichlor. These stabilized chlorines have about 50-58% CYA in their formulas.

2. Why use cyanuric acid?

CYA provides is a huge benefit to chlorine. CYA can extend the life of free chlorine by as much as 8 times in direct sunlight. For outdoor pools, that’s a game changer. That said, CYA is not to be used in an indoor pool.

Conventional wisdom in the pool business—at least, until recently—suggests an ideal range of CYA to be 30-50ppm, with a minimum of 10ppm and a maximum of 100ppm. Ranges vary, depending on state laws. We at Orenda recommend a little as possible (30ppm or less, ideally). Why do we differ? Because we recognize the need for chlorine to have longevity in sunlight, but also recognize its impact on sanitation. Additionally, with enzymes, chlorine levels can be minimal while maintaining a strong ORP.

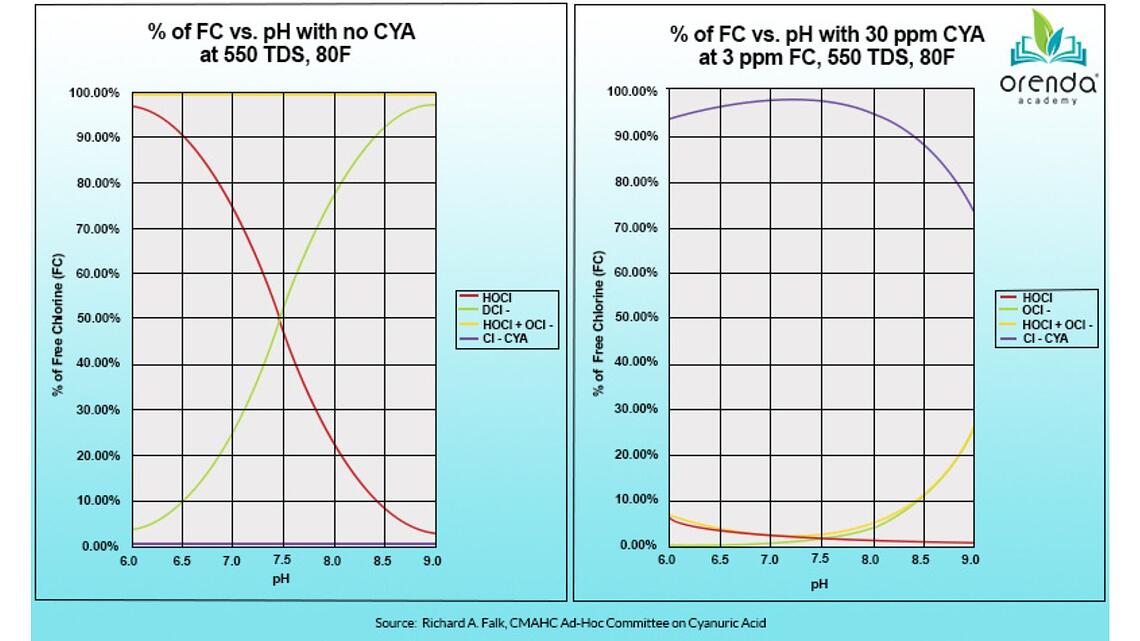

Dosing a CYA properly is a matter of knowing how much free available chlorine (FAC) you want protected, and how many gallons of water are in the pool. Sources suggest it takes about 10ppm CYA to protect 1 to 1.5ppm FAC, but we have not yet found a definitive answer on that. We DO know, however, that even small amounts of CYA can protect the vast majority of hypochlorous acid (HOCl), which is the strong, killing form of chlorine:

Source: The Chlorine/CYA Relationship and Implications for Nitrogen Trichloride, by Richard Falk

The left chart is without CYA. At 7.5 pH, half the chlorine is strong HOCl, and the other half is weak OCl-. On the right chart, the percentage of HOCl plummets to about 3%, meaning about 97% of chlorine is bound to CYA as an isocyanurate. This is good for protection, but it slows chlorine down for sanitization and oxidation.

The problem is not the stabilization of chlorine. It’s overstabilization. When water evaporates, CYA stays behind and stays in the water for a long, long time. This can be considered a benefit for some…but it can also be a problem down the road because the CYA will accumulate. For the most part, CYA levels can remain very stable if you’re not adding more of it to the water. The problems occur when CYA levels get too high.

3. Problems with cyanuric acid

Weaker, Slower Chlorine

Since chlorine is the front-line defense against germs and diseases in water, weakening it is a bad idea. Not only does chlorine have to overcome the oxidant demand before sanitization can happen, there is approximately a 7.5% chlorine reduction factor with cyanuric acid against algae. So let’s put this formula into the real world. If you have 100ppm CYA, your new minimum to stay ahead of algae growth is approximately 7.5ppm chlorine. Can you sustain that?

As mentioned earlier, CYA stays in the water for a long time. The easiest and most affordable way to reduce cyanuric acid is to drain the pool — at least partially. Some products claim to reduce CYA as well, but like any chemistry, there are reactions for every action. We won’t get into the weeds on the chemistry, but it involves many byproducts and steps to address them.

Misleading reading

Let’s now talk briefly about how ORP sensors and test kits can be fooled by cyanuric acid. Increasing cyanuric acid lowers ORP. Yet, if you measure free available chlorine on a DPD test kit, the chlorine shows up as free available chlorine (FAC). Why the inconsistency in results? We can explain.

ORP stands for oxidation-reduction potential. ORP sensors are probes that instantly measure the conductivity (in millivolts, mV) of water. They sense chlorine, but not chlorine attached to cyanuric acid. As a result, ORP may be lower, even if free chlorine remains the same. So what will the pool chemical controller do when the ORP levels are too low? Add more chlorine. Sometimes it takes additional calibration of the controller and sensors to get things operating right. This is something to be aware of if you have chemical automation.

Aggressive Water (LSI)

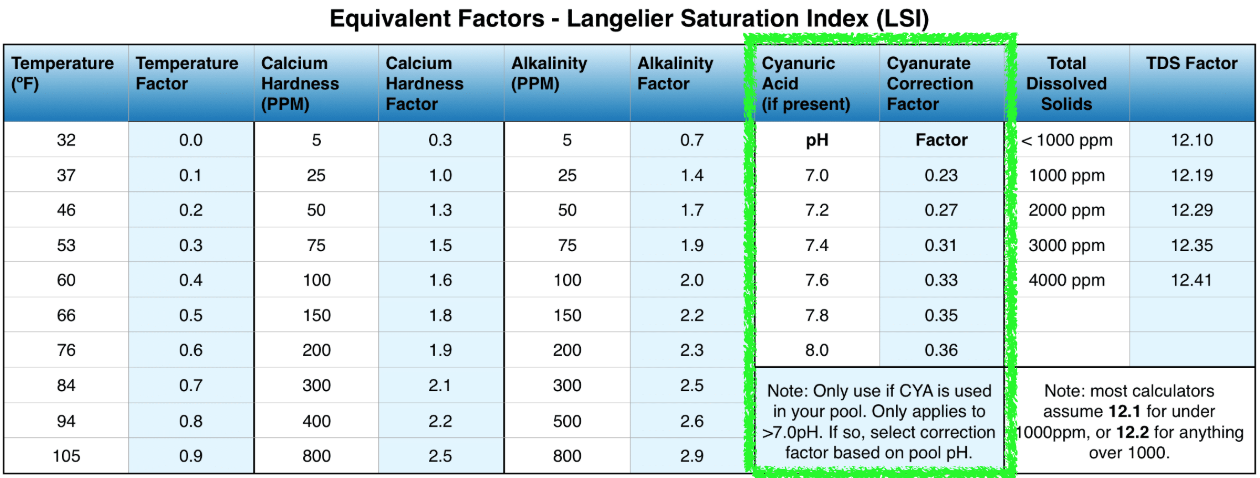

Another very important thing to understand about CYA is its impact on the Langelier Saturation Index (LSI). The higher the CYA, the lower the LSI. Why? Because CYA actually contributes to total alkalinity (it’s called cyanurate alkalinity). To accurately calculate the LSI, we need to know the carbonate alkalinity, which requires removing the cyanurate alkalinity from the total alkalinity. See the chart below and look at the correction factors, then we will go through the formula.

We need to remove cyanurate alkalinity from total alkalinity to find the carbonate alkalinity. The rule of thumb, as you can see in the chart, is to remove about 1/3 of the CYA ppm from the TA ppm. It looks like this:

TA ppm – (CYA ppm x [CYA correction factor @ pH of the water]) = Carbonate Alkalinity

or, the 1/3 rule of thumb:

TA ppm – (CYA ppm ÷ 3) = Carbonate Alkalinity

Let’s do an example to show how severely high levels of CYA can impact the LSI. In this example, let’s use 100 ppm total alkalinity, a 7.4 pH, and 90 CYA:

100 ppm – (90 ppm x [0.31]) = ? ppm

100 – (27.9) = 72.1 ppm Carbonate Alkalinity

That may not be a severe enough example. How about we use a pool that has been using trichlor for a few years…

100 ppm – (200 x [0.31]) = ? ppm

100 – (62) = 38 ppm Carbonate Alkalinity

The last example shows us how trichlor pools tend to be more aggressive–not only because of trichlor’s low pH, but because of accumulated CYA’s severe impact on the LSI. Don’t worry though, the Orenda App’s LSI Calculator takes care of all of this math for you. Just input your pH, measured total alkalinity and CYA, and all of this equation is factored in automatically.

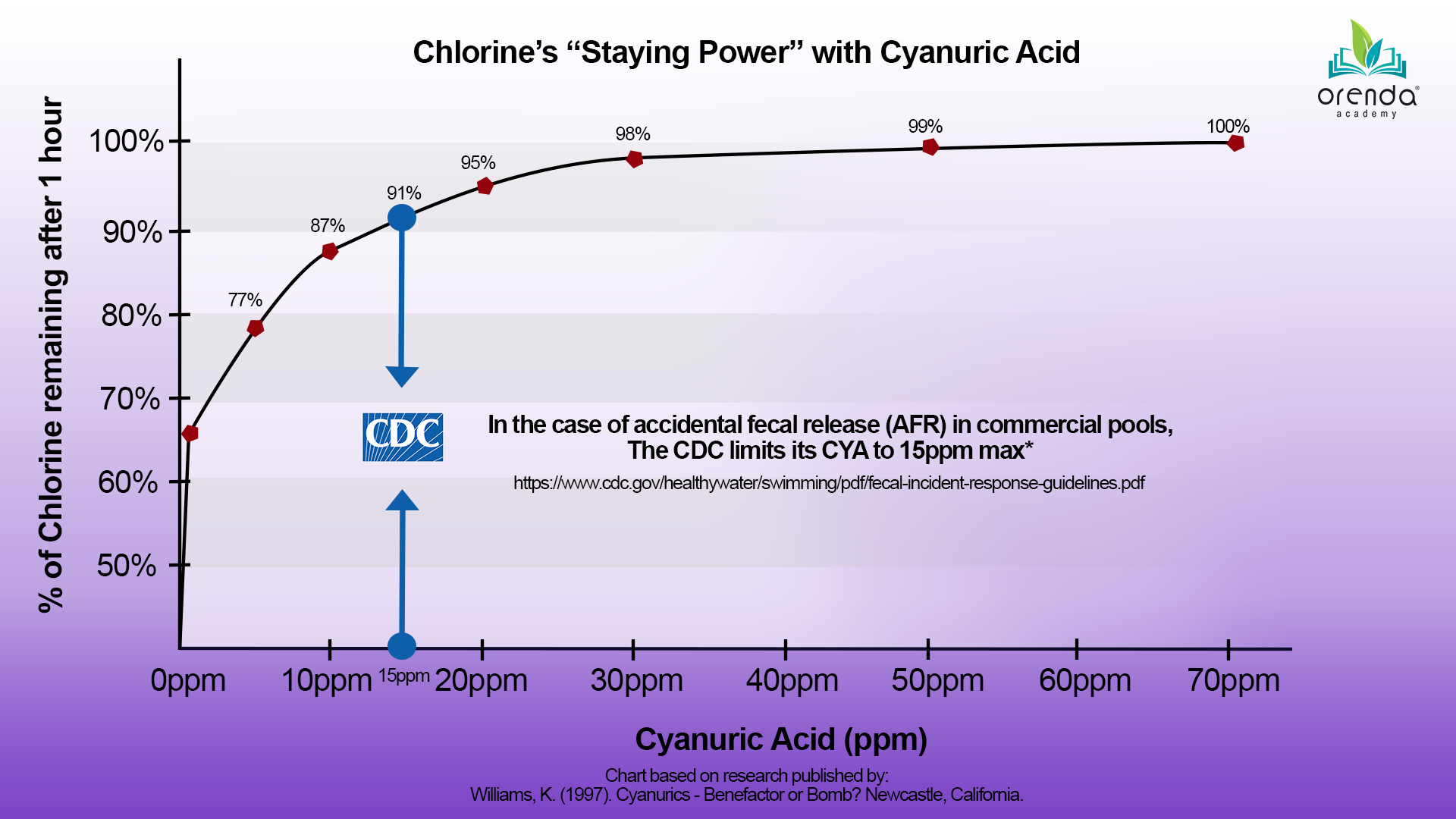

4. The CDC regulates CYA levels

What is the limit for CYA? Well, according to the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC), it’s 15 parts-per-million. Specifically, in the event of a fecal incident, the pool’s CYA level cannot exceed 15ppm. But do you know of any neighborhood summer pools that can get through their entire season without a single fecal incident?

Better to be safe and prepared than be shut down by the health department. From the CDC: In case of a fecal incident, close the pool, and CYA levels can no longer exceed 15ppm. This limit was decided for practical reasons. Sure, you could have more CYA in the water, but the levels of chlorine needed to accomplish the killing of a disease like crypto would be insanely high.

Why the CDC CYA limit happened

It’s very simple: chlorine stabilizers (like CYA) slow the rate that free chlorine kills pathogens. In the event of a fecal incident, sanitation is paramount to quelling diseases like cryptosporidium. CYA just gets in the way. Technically, you can have as much CYA as you want, as long as you maintain the FC:CYA ratio. But against a chlorine-resistant disease like crypto, it becomes impractical (if not impossible) to kill it with high levels of CYA.

Let’s get real here. If you’re treating outdoor commercial pools, keeping CYA under 15ppm is really hard to do. We get it. But that’s not an excuse for ignoring the CDC’s mandate. So what can we, as industry professionals, do to comply with this new CYA regulation? It’s our opinion at Orenda that the CDC’s 15ppm limit—while it is a painful change for many—offers an opportunity for new thinking. Pools have been operated the same way for so long; changing the way we think about water can be a good thing.

5. CYA can remain even after you drain

We have heard numerous first-hand stories of draining high cyanuric acid pools. For example, a service tech had a homeowner with a pool over 100ppm CYA. Drained the pool completely, and refilled it. Without adding anything to the pool yet—besides tap water—the CYA level was 30ppm the next morning.

We did some research. In not-so-scientific terms, we interpret the findings to mean that some CYA can stay behind when draining a pool. It can deposit itself on the pool surface as the water drains, and wait to be reabsorbed when refilled. We are not sure what it looks like or feels like, but it explains the mystery CYA in a newly refilled pool. Could it be that CYA is left behind like salt or other minerals? It seems possible…but we will continue to look into it. If you’re a chemist or cyanuric acid expert, please weigh in and contact us. We’d love to know more about it.

Conclusion

Stabilization is not the problem … overstabilization is. Avoid overstabilization and it will be much easier to maintain a clean and healthy pool.